The Environment and Christian Responsibility

Monday, 17 July 2006

Tyger Tyger burning bright,

In the forests of the night;

What immortal hand or eye,

Could frame thy fearful symmetry?

In what distant deeps or skies,

Burnt the fire of thine eyes?

On what wings dare he aspire?

What the hand dare seize the fire?

In what distant deeps or skies,

Burnt the fire of thine eyes?

On what wings dare he aspire?

What the hand dare seize the fire?

And what shoulder & what art,

Could twist the sinews of thy heart?

And when thy heart began to beat,

What dread hand? & what dread feet?

And what shoulder & what art,

Could twist the sinews of thy heart?

And when thy heart began to beat,

What dread hand? & what dread feet?

What the hammer? What the chain?

In what furnace was thy brain?

What the anvil? What dread grasp

Dare its deadly terrors clasp!

What the hammer? What the chain?

In what furnace was thy brain?

What the anvil? What dread grasp

Dare its deadly terrors clasp!

When the stars threw down their spears

And water'd heaven with their tears:

Did he smile his work to see?

Did he who made the lamb make thee?

When the stars threw down their spears

And water'd heaven with their tears:

Did he smile his work to see?

Did he who made the lamb make thee?

Tyger Tyger burning bright,

In the forests of the night:

What immortal hand or eye,

Dare frame thy fearful symmetry?

Tyger Tyger burning bright,

In the forests of the night:

What immortal hand or eye,

Dare frame thy fearful symmetry?

There is something magical, mysterious, even marvelous about the tiger,

as William Blake's 1794 poem indicates. The tiger is a perfect alpha

predator, able to leap ten meters from a standing position, a ferocious

killer. The largest of all the cats, it is both feared for its strength

and revered for its beauty. Despite its prowess as a hunter, or perhaps

because of it, the tiger has been brought to the brink of extinction by

its only enemy, humankind. Three of eight tiger subspecies have

disappeared in the last century (the Bali tiger in the 1940s, the Caspian

tiger in the 1970s, and the Javan tiger in the 1980s), and only between

5,000 and 7,000 tigers remain in the wild, hunted for their hides and

their organs, which are used in traditional medicines.

Why is the fate of the tiger an appropriate topic for Christian

reflection? The tiger reflects God's ingenuity and aesthetic sensitivity.

It is a fearsome, beautiful animal that humans may hunt to extinction

within a few decades. Some people, including Christians, think that

humans have the right to do whatever they want to do to the planet, but in

doing so, they misunderstand Gen 1:28:

God blessed them, and God said to them, "Be fruitful and

multiply, and fill the earth and subdue it; and have dominion over the

fish of the sea and over the birds of the air and over every living thing

that moves upon the earth."

The Hebrew word for "subdue" can have violent overtones (rape), but

parallelism with "have dominion" softens the meaning in this context.

Some scholars believe that the root meaning of the second word is "to

wander about, as a shepherd guiding his sheep." If that is true, then the

emphasis of this verse is that the world is not to be violated but rather

used for the benefit of all. The Septuagint (Old Greek) translation uses

a verbal form related to the noun usually translated "Lord," suggesting

that human beings are to treat the planet as though they were

representatives of the Lord, that is, with care, concern, and wisdom.

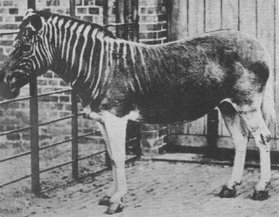

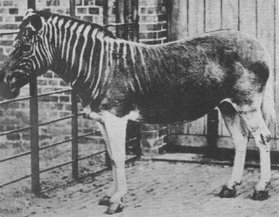

The extinction of the tiger would clearly be a great loss to the world,

but is the same true of the ivory-billed woodpecker, the California

condor, or the quagga (the last already extinct)?

Let's look at Psalm 148.

1 Praise the Lord!

Praise the Lord from the heavens;

praise him in the heights!

2 Praise him, all his angels;

praise him, all his host!

3 Praise him, sun and moon;

praise him, all you shining stars!

4 Praise him, you highest heavens,

and you waters above the heavens!

5 Let them praise the name of the Lord,

for he commanded and they were created.

6 He established them forever and ever;

he fixed their bounds, which cannot be passed.

7 Praise the Lord from the earth,

you sea monsters and all deeps,

8 fire and hail, snow and frost,

stormy wind fulfilling his command!

9 Mountains and all hills,

fruit trees and all cedars!

10 Wild animals and all cattle,

creeping things and flying birds!

11 Kings of the earth and all peoples,

princes and all rulers of the earth!

12 Young men and women alike,

old and young together!

13 Let them praise the name of the Lord,

for his name alone is exalted;

his glory is above earth and heaven.

14 He has raised up a horn for his people,

praise for all his faithful,

for the people of Israel who are close to him.

Praise the Lord!

Unlike many psalms of praise, this one says little about the reasons

for praising God: the psalmist assumes that the worshiper already knows

reasons to praise God. Instead, what he focuses on is the matter of

who should praise God. Praise begins in the heavens with the

angelic beings, and it moves to the sun, moon, and stars. Even the waters

above the heavens are called to praise God. From there, the psalmist moves

to the earth, calling on the powers of fire, hail, snow, and frost to

praise God, alongside the sea monsters of the deep. Then it is the turn of

the mountains and hills, fruit trees and cedars, wild and domesticated

animals, creeping things (reptiles and amphibians) and birds. Finally,

after all the inanimate and all other animate beings have had their chance

to praise God, the psalmist turns to humans beings. Both rulers and

ordinary people are called on to praise God, men and women, old and young.

I find this psalm fascinating, because, like several others, it calls upon

physical objects and all kinds of animals to praise God. It raises the

question, how can the stars, or snow, or a whale, or a cedar tree, or a

horse, or a Komodo dragon praise God? This is not an idle question, for it

is central to our understanding of a theology of creation.

Although it is a question that is much too big to answer in the short

time we have together this morning, let me suggest some ways in which we

might think about the meaning of creation's praise of the Creator. Before

we can proceed with examining how different types of animate and inanimate

beings can praise God, we first have to define praise in this context. If

praise in a human context means attributing value to a worthy God, then we

can think of non-human praise as ways in which creation points to the

goodness and wisdom of God. For example, if we believe that God's will

lies behind the organizational structure of the universe, then objects

like the sun, moon, and stars "praise" God by revealing to both casual

observers and dedicated astronomers the intricacies of the created order,

from the universe itself--or what we can observe of it or theorize about

it--to the tiniest subatomic particle, and from the Big Bang to the end of

the universe as we project it. Snow and hail and rain praise God by

revealing the divine goodness in providing the fresh water that humans,

animals, and plants alike need for survival. Even such destructive forces

as hurricanes and earthquakes praise God in the sense that they remind us

that the world has mechanisms that are designed to renew and recycle the

resources that God has given us. Ecologists know that periodic hurricanes,

in an era before human encroachment on the sea coasts, renewed coastlands

and wetlands, just as naturally occurring forest fires are part of the

natural cycle of life in the woodlands. Similarly, earthquakes are part of

the natural movement of tectonic plates, which results in mountain

building, continental drift, long-term climate change, and ultimately in

recycling the earth's crust.

Plants and animals praise God by being exactly what they are: organisms

that rely on the sun and each other for energy to survive and multiply.

Their complexity of internal structure and external interaction with other

species in the web of life reveals the brilliant mind of God. A corollary

of this observation is that when humans exterminate a species, either

directly, as in the hunting to extinction of the quagga, or indirectly, as

in the habitat destruction that has driven wild tigers, California

condors, and ivory-billed woodpeckers to the brink of extinction, we are

diminishing the chorus of living beings that give praise to God. Although

we started with a definition of praise derived from human interaction with

the divine and moved into a discussion of non-human praise, we can now

move the other direction and ask ourselves what we humans can learn about

praise from the rest of God's creation. Probably we can learn many things,

but one lesson stands out for me. We tend to view praise as something that

is exclusively verbal--whether spoken, sung, or thought--but our inquiry

into non-human praise has shown us that created beings without the

capability of language are able to praise God without any problem.

Therefore, I would suggest that human praise, like non-human praise,

should be defined primarily as ways in which we humans can point to the

goodness and wisdom of God. We can do so by caring for God's creation, by

loving our neighbors, and by leaving the world a better place than we

found it. In short, we should live lives of praise to God, and in that

endeavor, we should remember that our words of praise are merely

icing on the cake.

In addition to extinctions, what other issues related to the

environment should be of importance to Christians? Here is a partial

list.

- global warming, which leads to the melting of the polar ice

caps, the submersion of the island nation of Tuvalu, the spread of dengue

fever and malaria, and the destruction of polar bear habitat

- pollution of air and water, as well as noise pollution and

light pollution

- deforestation, the destruction of topical rainforests,

temperate forests, extinctions, soil erosion, and mudslides

- loss of biodiversity, which results in crops becoming

increasingly susceptible to new diseases

What is our responsibility as Christians in regard to the environment?

The short answer is this: we are to care for the earth as God's

representatives. Here are some practical things that everyone can do:

- recycle

- pick up litter in your community

- conserve energy (by buying more energy-efficient cars, modifying your

heating/cooling habits, car pooling)

- donate to worthy environmental causes

- educate your family and friends about the environment

- support public officials with responsible environmental records and plans

- speak out on environmental matters

- learn more about important environmental issues

- lead your church through a biblical, theological study on Christians

and the environment

- celebrate Earth Day every April

- lower your ecological footprint (i.e., your impact on the environment)

- learn about one critically endangered plant or animal in your area (in

my area, this includes the Texas blind salamander, Leon Springs

salamander, Helotes mold beetle, Government Canyon cave spider, whooping

crane, and Mexican long-nosed bat--see the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species

for other examples)

Let me end with another word about extinction. The loss of any species

is a permanent loss from the created order. It diminishes the beauty of

the earth, the glory of creation, and the enjoyment of humanity. On

September 7, 1936, the last thylacine on earth died in the Hobart,

Tasmania, zoo. Also known as the Tasmanian tiger, like this old video, its voice is forever silent. What species

is next? What will we do to preserve the great chorus of creation

praising God?

This article is a version of an address delivered

in chapel at the Baptist University of the Américas in February

2006.

© Copyright 2006, Progressive

TheologyProgressive Theology

In what distant deeps or skies,

Burnt the fire of thine eyes?

On what wings dare he aspire?

What the hand dare seize the fire?

In what distant deeps or skies,

Burnt the fire of thine eyes?

On what wings dare he aspire?

What the hand dare seize the fire?

And what shoulder & what art,

Could twist the sinews of thy heart?

And when thy heart began to beat,

What dread hand? & what dread feet?

And what shoulder & what art,

Could twist the sinews of thy heart?

And when thy heart began to beat,

What dread hand? & what dread feet?

What the hammer? What the chain?

In what furnace was thy brain?

What the anvil? What dread grasp

Dare its deadly terrors clasp!

What the hammer? What the chain?

In what furnace was thy brain?

What the anvil? What dread grasp

Dare its deadly terrors clasp!

When the stars threw down their spears

And water'd heaven with their tears:

Did he smile his work to see?

Did he who made the lamb make thee?

When the stars threw down their spears

And water'd heaven with their tears:

Did he smile his work to see?

Did he who made the lamb make thee?

Tyger Tyger burning bright,

In the forests of the night:

What immortal hand or eye,

Dare frame thy fearful symmetry?

Tyger Tyger burning bright,

In the forests of the night:

What immortal hand or eye,

Dare frame thy fearful symmetry?